Building Models of the Developing Brain

By Michael B. Fernando

Our existence, from perceiving the outside world to processing our emotions, is executed by our brain, a complex organ made up of diverse cell types and tissues. Though complex, the brain begins as just a small number of cells, called “stem cells”, during development.

Stem cells are the body’s starting material. They are termed “pluripotent,” meaning that they can give rise to every kind of cell in your body. Over time they morph into a variety of other types of brain cells, including neurons, which send chemical messages to each other about our internal and external world, and glial cells, which support and protect neurons.

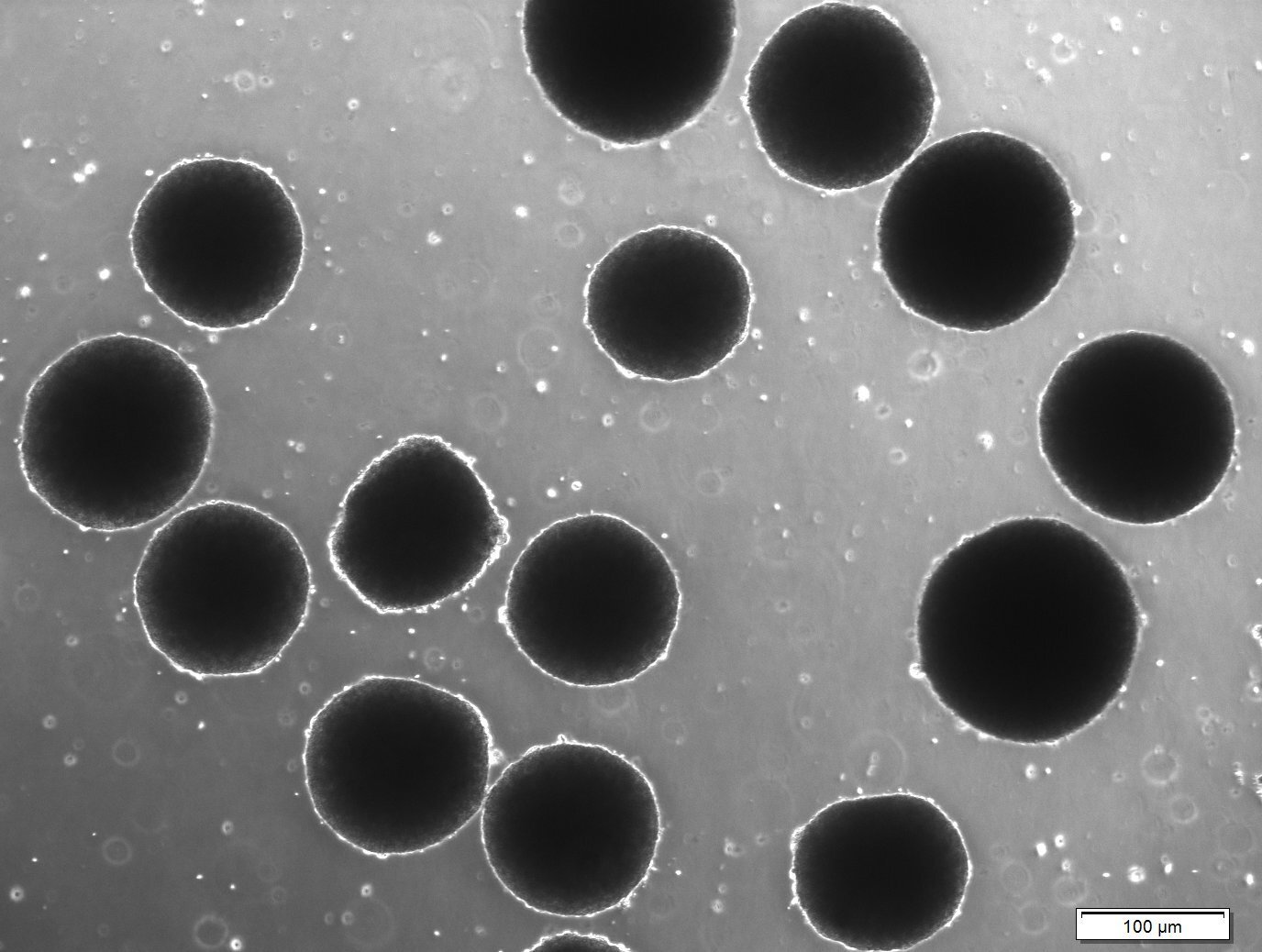

Brain organoids grown in a dish. Image courtesy of Aleta N. Murphy from the laboratory of Professor Kristen Brennand.

In the developing brain, stem cells start as a small collection of cells, but ultimately self organize and sort into distinct regions. This allows them to perform specialized functions, including movement, speech, and memory recall.

Brain disorders like Autism and Schizophrenia often result from genetic abnormalities during brain development. In order to establish treatments we must first study what is going awry. However, it is challenging to access live human brain tissue, especially during neurodevelopment.

In other fields, for example cancer biology, it is easier to sample cancerous tissue from patients. In neuroscience, it is not easy to access brain tissue from living people. For this reason, neuroscientists and stem cell researchers have resorted to creating new models and platforms by which modeling neurodevelopment is feasible, and in a non-invasive way.

One exciting new avenue of research is using stem cells made from individuals to generate “organoids.” Organoids are self-organized three-dimensional structures that mimic aspects of the developing brain.

While it sounds like something straight out of a sci-fi movie, scientists have discovered that these 3D models can be slowly patterned to resemble sub-regions of the brain, like the forebrain, midbrain, or the thalamus.

These “building blocks” can then be fused to one another or assembled into model circuits, which give scientists a new window to study key aspects of neurodevelopment.

Inside a brain organoid, colors represent immunostained biological markers (Red = SOX2, a marker for stem cells; Green = MAP2, a marker for mature neurons; Yellow = KI67, a marker for dividing cell). Image courtesy of Aleta N. Murphy from the laboratory of Professor Kristen Brennand.

Several labs have been able to generate organoids from not only healthy individuals, but patients who suffer from brain disorders. For example, a team of researchers at Stanford University has been able to obtain stem cells from patients diagnosed with a rare disorder known as Timothy Syndrome.

Timothy Syndrome is a genetic disorder that often results in Autism. Using stem cells from patients with Timothy Syndrome, this lab uncovered dysfunctions in the way certain brain cells move within a circuit and communicate with other cells.

By comparing brain organoids from these patients to healthy individuals, scientists have been able to identify malformations or dysfunctions in brain organogenesis (the making of organs), which will ultimately help us pinpoint opportunities for clinical therapies.

Michael B. Fernando is a PhD student at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and a Gilliam Fellow of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. He is interested in understanding how the brain organizes all of its connections and in his free time, is a major foodie, loves to explore the city, and play intramural soccer with his friends.

Edited by Denise Croote, PhD